Songs of Power and Passion

-

By Gowri Ramnarayan

Aruna Sairam introduced the Chennai audience to the beautiful compositions of the abhang poets

This is not a recital for reviewing. How do we review a performance of devotional music? By raga? Each abhang starts under the wing of a raga, say Bhimplas or Brindavani, but runs into phrases tumbling over one another with notes and arrangements, their emphasis and timbre suggesting a range of other ragas and raginis. These melodic branchings are so continual and diverse that there is no keeping track of even raga shadows.

So, do we look at the tala structures? Though Aruna Sairam's abhang concert at The Hindu Friday Review November Fest had an array of drummers from mridangam, ghatam and tabla to pakhawaj, cymbals, and a plethora of additional percussion, the rhythms themselves were simple, repetitive, familiar, mostly of four, occasionally three, easy for the audience to keep beat, as they did, several times during the concert.

Aruna's superb communication skills not only packed the Music Academy but retained the crowd even after the interval, a feat indeed in Chennai.

Her celebration of Panduranga Vittala, with songs of power and passion by the saints of Maharashtra singularly obsessed with the God, had a stage where peacock feathers swung on banners, in lights sea green and riverine blue. The singer's saree too had Krishna colours of aquamarine and green.

The array of accompanists made you recall old time reports of legendary Naina Pillai's full bench concerts. But there the similarity ended. There were to be no rhythm explosions or competitive fireworks. No complicated tala patterns to tantalise. The team — Anish Pradhan (tabla), Prakash Sejwal (pakhawaj), Pratap Raat (additional drums) Sudhir Naik (harmonium), K.Murugabhoopathy (mridangam), H.N.Bhaskar (violin), S.V.Raman (ghatam) worked smoothly — providing light and shade for the voice. Aruna's pithy introduction to each song kept the interest alive for the majority of the audience who knew little about abhangs, and less Marathi.

Starting with the mandatory invocation to Maharashtra's beloved Ganapati, Aruna plunged into Namdev's "Tirtha Vittala", the obvious choice to introduce the omnipresent Krishna-obsession of the abhang composers. Later, she was to raise chuckles with another poet who saw Vittala in the radishes and onions he picked in his garden. "Brindavani venu" centralised the motif of the tiger jostling with the cow, forgetting their natural enmities, mesmerised by Krishna's flute by the Yamuna woods.

With the followers of the Varkari sampradaya (of people who see Vittala in everything) were drawn from every walk of life — potters, jewellers, farmers — the imagery too came from their fields of work. This made the abhangs diverse, class-transcending and earthy. The approach and temperament of the abhang composers also differed significantly. Aruna not only spoke about the "atma vichar", internal search of Gnaneshwar, and the emotional intensity of Namdev, she also tried to demonstrate them through the singing. Tukaram, Eknath and Samarth Ramdas got their turns. A notable omission was Janabai.

One of the pan-Indian images of the bhakti poets describes the Lord not only as the eternal lover and protector, but also as the loving mother who spares no efforts to make her child safe and happy. Vittala as the compassionate mother — janani, jagadamba — was portrayed in a moving abhang. The "Vittala" finale was intoned again and again, with mounting frenzy, with the tabla and the ghatam evoking the syllables on fingers. During "Gnaniyantsa raja", Tukaram's tribute to Gnaneshwar, we saw the audience turning participants in a sing-along, clap-along experience. Aruna's journey took her to Rajasthan with Mirabai's "Liyo Govinda mol". And to Bengal, awakening Kali Ma with a song of rising resonances. Karnataka was accorded a toe-tapping "Bhagyada Lakshmi baramma". Nor was Mumbai's Ganapati bappa forgotten. Zestful Natya Sangeet got a bow with "Narayana, rama ramana" in a tune close to Sarasangi, prefaced by a reference to the influence of "karnatiki" raags on this unique genre of theatre music.

The post interval session had the audience rocking with the energy on the stage. But the song best displaying the singer's skills in mood swings, in tempos slow and fast, long karvais and brisk beats, was reserved for Ambabai of Kolhapur. Intent individual prayer and collective chanting effects here gave the song a rich texture of its own. The mood of the final arati was not new to Chennai. It invoked the margazhi morning bhajanai frenzy — jazzed up with tinted lights flashing on the stage Woodstock style.

Aruna's full-throated singing, her mighty karvais using the whole sound production system in the human body, were perfectly suited to what she sang that day. Her reverberant voice was able to hold its own with the many accompanists from the north and the south. The accompanists, on their part, knew they were not displaying concert skills but supporting devotional music. They kept the rhythms and tunes basic — and very melodious on the violin. They empathised with each style, mood and the mid-song rhythm shifts. Aruna Sairam emerged from the evening as an artiste trained in the classical school, who respected other musical genres, and enjoyed adventuring into their territories.

Related Albums

Trialogue

Published : 2012

By : Glossa Music

Rang Abhang

Published : 2011

By : Nadham Music Media

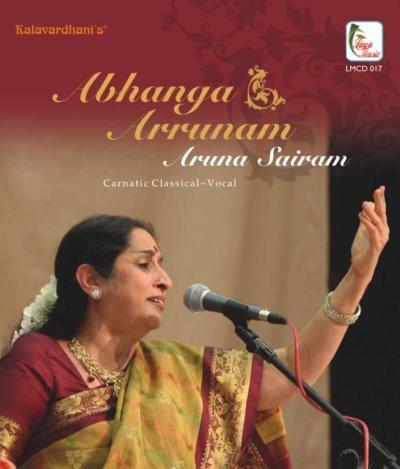

Abhanga Arunam

Published : 1994

By : Kalavardhini's

Related Concerts

- Bolava Vitthal - Celebrating Ashadhi Ekadashi An Evening of Abhangs

On : Friday, July 27, 2018 - Sambho Shiva Sambho

On : Monday, March 7, 2016 - Chennai December Season 2018 - Carnatic Classical Vocal

On : Wednesday, December 26, 2018 - Music Academy 92nd Annual Conference Inauguration

On : Saturday, December 15, 2018

Photos

Photos PDF

PDF