I Try to Enjoy Myself

-

by Baradwaj Rangan

Whether it’s ‘abhangs’ from western India or medieval music from the Western world, Carnatic singer Aruna Sairam believes that her art is as much for herself as her audience.

AUG 15, 2005 – THE WORLD CAPITAL OF CARNATIC MUSIC today is Chennai, a city mostly of Tamils. The popular concert repertoire, though, is mostly in Telugu. Then, thanks to the odd Meera bhajan, the odd Bhaja Govindam recording, the odd Purandara Dasa kriti, Hindi and Sanskrit and Kannada have made their presence felt. Now, with abhangs finding favour, a Marathi influence has crept in. It’s enough to make you wonder why professors of sociolinguistics worldwide haven’t already made a beeline to Chennai during the December music season, researching theses titled “The Assimilation of Western and Northern Languages into the Music of Southern India, or “How the Mumbai Local Trains Bridged the Gap between Tukaram and Thyagaraja.

The latter would be Aruna Sairam’s story. I ask her one afternoon how she’s become “that lady who sings abhangs, and she laughs. “At one point, I thought growing up in Mumbai was a great disadvantage in trying to be a Carnatic classical singer. In hindsight, it’s proved a big advantage. I used to take the local trains, where employees of the railways, textile mills, and so on, would sing abhangs – with total faith, with total abandon – all through the journey. It was some of the most amazing music I’d heard. I got interested, and my mother would invite abhang singers home to perform. After all that exposure, I wanted to sing some of that music here, and after a couple of concerts with abhangs, I haven’t looked back.

But abhangs aren’t exactly “Carnatic music. I mean, does a typical, traditional rasika in typical, traditional Mylapore just get up one evening, in the thick of December, and proclaim, “Oh, let me listen to abhangs over some piping hot filter coffee! The way Aruna sees it, though, “Concert music is just one phase of Carnatic music. In South Indian music culture, there’s something called the Bhajana Sampradaya tradition, containing songs from all over – Ashtapadi, Kabirdas, Meerabai, abhangs… A pan-Indian repertoire under one umbrella, so to speak. And people have been singing these songs day in and day out. So long as it’s classical, it’s not cheap, it’s not vulgar, it’s not deviating from certain norms, and it’s got bhakti rasa, why not? After all, in my concerts, you’re still going to find basic elements like a ragam-thalam-pallavi, a Dikshitar or Shyama Shastri or Thyagaraja. In addition, I do a couple of things, which, to me, completes the picture of what I understand as music.

So bhakti rasa is what she’s after, and when I wonder if there isn’t more of shringara in the Ashtapadi, if that mood wouldn’t be more the domain of a thumri, for instance, Aruna clarifies, “The way I understand bhakti, all the nava rasas are brought under it – and that’s fascinating. It’s a celebration of life. Nothing is excluded from this bhakti – unlike in some Western countries, where they have tried to segregate these things. Perhaps that underlines the unification Aruna has been attempting, between their and our systems of music. “I first went to Europe as a kind of visiting professor in a German University. Slowly, I started performing in France – but these were traditional concerts, with my usual group from here. Artistes from there came to these concerts, and that’s how I stumbled upon Dominique Vellard, with whom I perform. He sings not contemporary classical but medieval music, which is very melody based. A song conforms mostly to one raga. So that works.

“That works. It sounds so simple when she puts it that way, almost indifferent to the differences between these systems of music. If, for us in the East, a scale is based on the sa, a flexible pitch, for them out West, it’s based on an absolute pitch, the fixed frequency of the note. But the twain can still meet, Aruna believes, “If the artistes doing the dialogue have an open-enough attitude. For instance, if Dominique stubbornly insists, ‘This song has to be sung with the starting note on this absolute pitch,’ then we can’t work around that. What we want to do is keep the spirit intact, so he’ll probably compromise, changing the pitch from F# to F. I may allow my piece to be truncated and interspersed with a verse from his song. But you have to decide how far you want to radiate your own roots and how far you will compromise. And if rules are broken, as they’re sure to be in this process, that’s just how it should be. “You learn the grammar precisely because you want to break rules. That’s what gives you your style. That’s what makes you an artiste.

She breaks rules for accommodating foreign audiences. Then she returns to Chennai and faces the toughest, most conservative of listeners. Then she’s off to Mumbai and Delhi, to a different set of expectations. So it’s no surprise that Aruna relies on audience psychology, and tailors concerts according to geography. “In Chennai, people listen to the music, but they also know the songs, who’s composed them, etc. As you’re singing, their mind is on its own track, based on all the exposure they’ve had to that song. You have to keep that in mind and choose pieces accordingly. In Mumbai, for example, they don’t understand the words. However, they’ll get the beauty of the lyrics because there is the common thread of bhakti throughout India. But when you go abroad, even that is absent. Their way of communion with God is totally different. So you can’t base your music on that particular point. Once you understand that, it’s completely gana rasa, that is, music for music’s sake.

Even so, while mentally switching from one type of audience to another, one type of music to another, there’s surely some kind of crossover, however subconscious. While singing in Chennai, say, she may bring in elements she’d normally use in Mumbai, which is exactly the sort of thing that doesn’t sit well with critics. Aruna agrees she was troubled by such thoughts once upon a time. “I used to go through a lot of trauma whenever I had to travel, just thinking of what I’d sing, what they’d understand. But after a point, when you keep meeting people and keep learning, you say, ‘Look, this is what I know. Overnight, I’m not going to learn anything new. So let me go out there and let my experience speak for itself.’ People around have constantly advised me to make music enjoyable for everyone, to demystify and simplify it. So the trauma is no longer there. If people criticise, let them. If the criticism points out something, I’d look at it seriously and try to grow. Otherwise, this is me. Why should I be ashamed of sharing what I am with you?

“Now, after ten years of being accepted as a performer, I’ve understood that music is not to be put on a pedestal. Classical music is sometimes very intimidating and elitist, but, with so much on television today, people still come to concerts. The music should reach out to every person who comes to listen to it, yet you should never underestimate your listeners. Just like you can’t talk down to people, you can’t sing down to them. You’ve got to sing for them – and for yourself. In my concerts, I try to enjoy myself and I also try to sing for my audience. Whatever you’ve learnt, if you’re able to say, ‘This is what I have but this is what I’d like to share,’ it will automatically radiate in your music. And I have to thank my audiences for making me understand that.

Related Albums

Trialogue

Published : 2012

By : Glossa Music

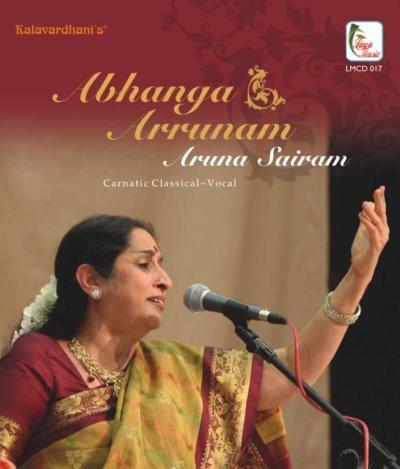

Abhanga Arunam

Published : 1994

By : Kalavardhini's

Rang Abhang

Published : 2011

By : Nadham Music Media

Related Concerts

- Bolava Vitthal - Celebrating Ashadhi Ekadashi An Evening of Abhangs

On : Friday, July 27, 2018

Photos

Photos PDF

PDF