From Madras to Chennai

-

by Jaithirth Rao

I left Madras in 1971 and was relieved. Tambrahm pomposity and garish Dravidian political cut-outs represented to me a parochial and avoidable combination. The heat, humidity and the malodorous Cooum river were only partially offset by the glorious beach. Over the years, I have often returned to newly christened Chennai. Prompted by resident historians, the redoubtable Muthiah and the effervescent Randor Guy, I have delved into its history (recorded and unrecorded) and its geography (spatial and metaphorical). My memories and reactions today are more mellow.

St Thomas Mount, the residence of the scary, larger-than-life, red-faced Tommies of my father’s generation, was in my time a place where Anglo-Indians with names like Alistair and Denzil lived and sent in their requests to Radio Ceylon’s ‘Listener’s Choice’. Their preferences were for Cliff Richards and Englelbert Humperdinck. The Thousand Lights Mosque built by the Prince of Arcot was and is a reminder of the creative presence of Mohammedan nobility and commoners in the city. Till not so long ago, most of the land in south Madras belonged to the descendants of two Shia courtiers in the Nawab’s retinue. The Khaleeli and Isfahani families have left their names on countless title deeds in the yellowing files of Ripon Building, the grand Indo-Saracenic structure, which houses the city corporation offices.

The erstwhile presidency capital had a strong Telugu presence. Some 20 years ago, I bought a flat from Pradeep Rao, a college-mate of mine, who if titles had not been abolished would have been the Raja of Pithapuram, an Andhra Zamindari.

The records indicate that the city owes many buildings, bridges and layouts to the far-sighted Armenian merchant-prince Coja Petrus Uscan. My ophthalmologist in Chicago was the one who told me that the first Armenian newspaper was published from Madras. So much for the by-lanes of history!

The city is not in denial about its British connection. Munro’s statue still stands next to Island Grounds. It was Sir Thomas Munro, Governor of Madras Presidency, who first in the Baara-mahals (literally “Land of Twelve Fortresses”, modern Salem District) and then elsewhere laid the foundations of an imperial dispensation more benign and less rapacious than in Bengal or the United Provinces.

Madras is also about cricket, not just international matches (I saw Gary Sobers score a brilliant 97 there), but also of humble league matches where some of us who did not play went to cheer and keep score. College days are special in retrospect. For me, Loyola was liberating in multiple ways. Francis and Raja, Srinivasan and Simon, Swaminathan, Bechtloff and Govindarajan opened up enchanted worlds. And of course, the college was full of brilliant persons, many of whom have gone on to heights of achievement.

With age, consciously or otherwise, one has a tendency to embrace the long-lost umbilicus and reach out to what must pass for roots. Carnatic music surely represents an aural throwback to amniotic seas. It is hard when one’s siblings can recognise a raaga from the first few notes of the aalapana. I confess that I cheat. I have a crib sheet that tells me the raagas of well-known compositions and I work backwards. I am completely at sea during the aalapanas although (given the vigorous shaking of my head) my neighbours in the auditorium will hardly guess this. Once the composition starts, my knowledge base is relatively secure. Of course, I knew all along that this was Kamboji or Brindaavana Saaranga.

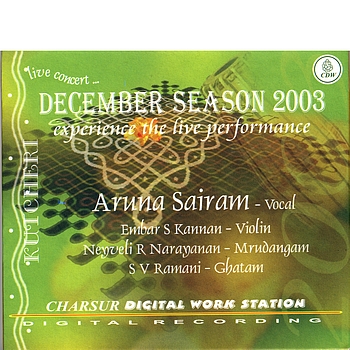

For two years in a row now, I have had the extraordinary luck of being in Chennai on winter days when my friend Aruna Sairam’s concerts have been scheduled. Last year, it was at the Mylapore Fine Arts Club and this year, at the Narada Gana Sabha, both bastions of classical music. The concerts were packed (standing room only) with listeners who actually paid for tickets. What a contrast to philistine Delhi, where even with the distribution of free passes, great artistes find half-empty halls. Aruna and several of her contemporaries are living proof that Carnatic music, while firmly rooted in classical traditions, has an amazing capacity to rejuvenate itself in multiple directions.

The writer is an observer and student of contemporary India jerry.rao@expressindia.com

Related Concerts

- Chennai December Season 2018 - Bharat Kalachar

On : Wednesday, December 19, 2018 - Valayapatti Kaasyap Naadhalaya 24th Year Music Festival 2018

On : Sunday, December 16, 2018 - Chennai December Season 2018 - Margazhi Maha Utsavam

On : Sunday, December 2, 2018 - Chennai December Season 2017 - Carnatic Classical Vocal

On : Tuesday, December 26, 2017

Photos

Photos